The power of monuments is evident whenever visitors can engage with the pieces in a personal way, but just as important is their ability to inspire a city or nation from afar. Sitting atop the Gellért Hill in Budapest, Hungary, the Liberty Statue (Szabadság-szobor) has been able to provide that engagement and inspiration ever since it was erected, but it was originally doing so for a different purpose. Since then, it has been transformed into a symbol that means something different and far more relevant to the city of Budapest and the nation of Hungary.

The power of monuments is evident whenever visitors can engage with the pieces in a personal way, but just as important is their ability to inspire a city or nation from afar. Sitting atop the Gellért Hill in Budapest, Hungary, the Liberty Statue (Szabadság-szobor) has been able to provide that engagement and inspiration ever since it was erected, but it was originally doing so for a different purpose. Since then, it has been transformed into a symbol that means something different and far more relevant to the city of Budapest and the nation of Hungary.

A Tribute to the Red Army’s Triumph

The Liberty Statue is a Soviet-installed statue complex that was first erected in 1947 in remembrance of the Soviet liberation of Hungary from Nazi forces. As memorialized elsewhere in Budapest, these forces caused a great deal of harm to the city and country during World War II. Originally known as the Liberation Monument, the central piece depicts a female figure holding a palm in the air and looking toward the east, in the direction of the Soviet Union. The 14-meter tall bronze statue that is supposed to represent liberty stands atop a 26-meter pedestal.

The Liberty Statue is a Soviet-installed statue complex that was first erected in 1947 in remembrance of the Soviet liberation of Hungary from Nazi forces. As memorialized elsewhere in Budapest, these forces caused a great deal of harm to the city and country during World War II. Originally known as the Liberation Monument, the central piece depicts a female figure holding a palm in the air and looking toward the east, in the direction of the Soviet Union. The 14-meter tall bronze statue that is supposed to represent liberty stands atop a 26-meter pedestal.

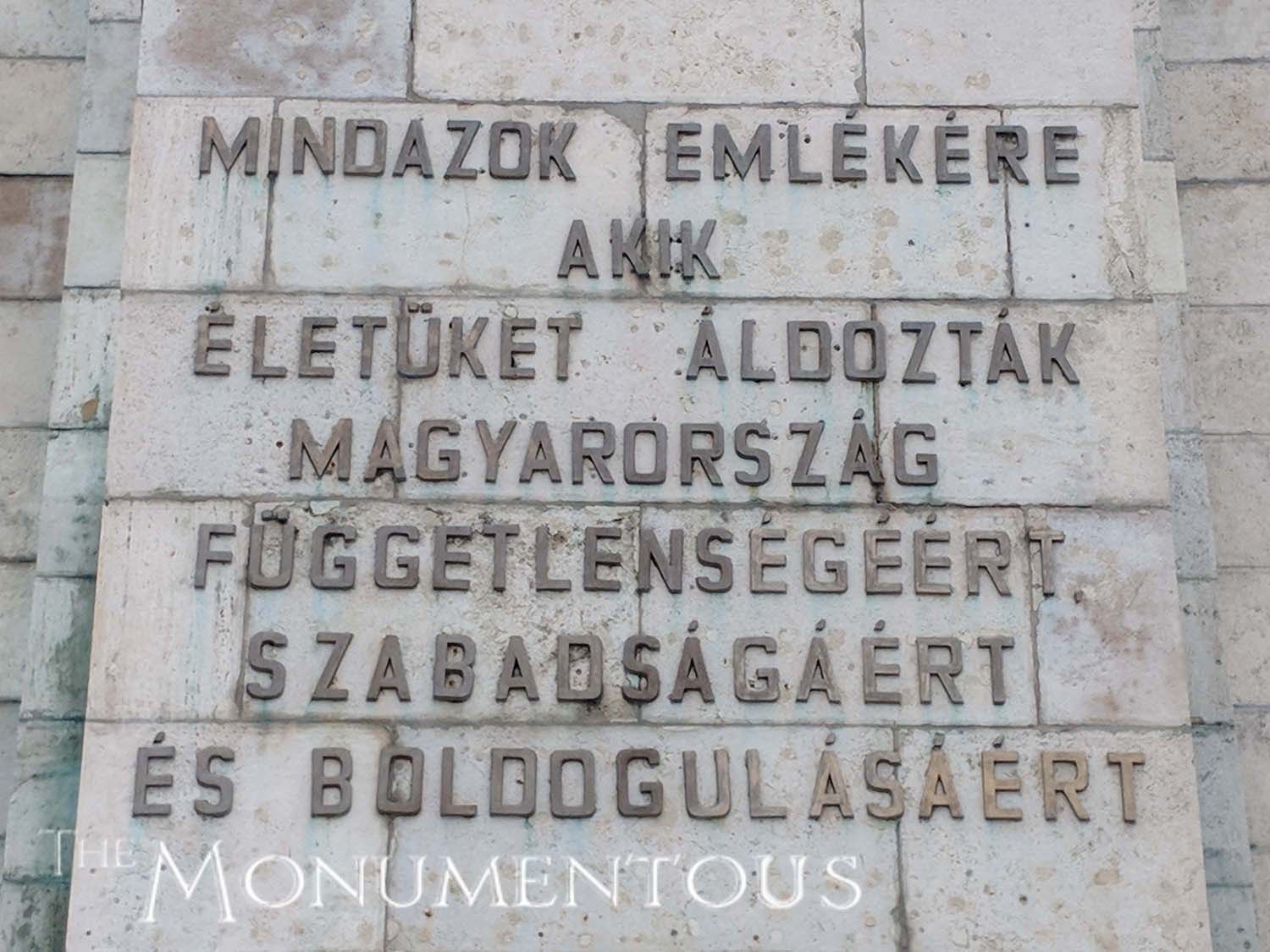

The defeat of Axis forces by the Red Army was officially proclaimed a “liberation”, which led to the name of the monument as well as the inscription on it which originally said: “To the memory of the liberating Soviet heroes [erected by] the grateful Hungarian people [in] 1945”. Numerous other statues appeared at the base of the piece, including statues of Soviet soldiers, a dragon slayer and a torch-bearer.

It wasn’t long before Hungarians began to view the Soviet Union as a similar occupying force though, and opinions about the monument began to change. One of the Soviet soldier statues was destroyed during Hungary’s 1956 Revolution, and the county’s 1989 transition to democracy compelled far more significant changes to the piece.

It wasn’t long before Hungarians began to view the Soviet Union as a similar occupying force though, and opinions about the monument began to change. One of the Soviet soldier statues was destroyed during Hungary’s 1956 Revolution, and the county’s 1989 transition to democracy compelled far more significant changes to the piece.

The Soviet soldier statues were relocated to Memento Park, although the dragon slayer and torch-bearer statues remained. The inscription on the monument was also changed to read: “To the memory of those all who sacrificed their lives for the independence, freedom, and prosperity of Hungary”. After the transition, the piece began to be referred to as Liberty Statue rather than Liberation Monument, further illustrating how it was being re-positioned for a new era of the country.

These significant and subtle changes to the Liberty Statue are indicative of the power it has been able to exert for residents and visitors, all of which stem from what the monument inspires, whether it’s viewed from near or afar.

Viewing and Experiencing the Liberty Statue

Gellért Hill is a large hill that overlooks the Danube River, which makes the Liberty Statue visible from numerous sites across Budapest. That vantage point made it a prominent feature of Budapest’s cityscape and influenced feedback around whether to keep or remove the piece after the Soviet troops’ withdrawal. The Liberty Statue remains a prominent fixture of the city, but that’s far from the only experience it provides.

Gellért Hill is a large hill that overlooks the Danube River, which makes the Liberty Statue visible from numerous sites across Budapest. That vantage point made it a prominent feature of Budapest’s cityscape and influenced feedback around whether to keep or remove the piece after the Soviet troops’ withdrawal. The Liberty Statue remains a prominent fixture of the city, but that’s far from the only experience it provides.

The Liberty Statue can be reached by bus or car, but ascending the hill on foot is the only way to see other monuments that are placed throughout Gellért Hill, as well as the parks, playground and incredible views of the city. Other large and small monuments like the Gerard of Csanád Monument can be seen from this vantage point as well.

The top of the Gellért Hill naturally has the best view, and also allows visitors to get up close with the Liberty Statue. The female figure holding a palm soars many meters in the air away from viewers, but it’s possible to have a much more personal experience with the other two statues. Visitors can pose in front of and near the dragon slayer and torchbearer statues, and can also clearly see the new inscription.

The top of the Gellért Hill naturally has the best view, and also allows visitors to get up close with the Liberty Statue. The female figure holding a palm soars many meters in the air away from viewers, but it’s possible to have a much more personal experience with the other two statues. Visitors can pose in front of and near the dragon slayer and torchbearer statues, and can also clearly see the new inscription.

Views of the Liberty Monument and city are far from the only things to do at the top of Gellért Hill though, as the Citadel is accessible while vendors are set up to allow visitors to do everything from buy food to shoot arrows. These examples illustrate just a couple of the multiple opportunities the monument has opened up for Budapest.

A Symbol of the Present-Day

Since it was built as a commemoration of Soviet triumph, questions about whether it made sense to keep or remove the Liberty Statue raged on for many years, similar to how other nations have tried to reconcile the history their monuments represent. The fact that the Liberty Statue is now seen as a symbol of Hungarian freedom illustrates the power these monuments have when it comes to influencing change and growth for a city and even an entire nation.

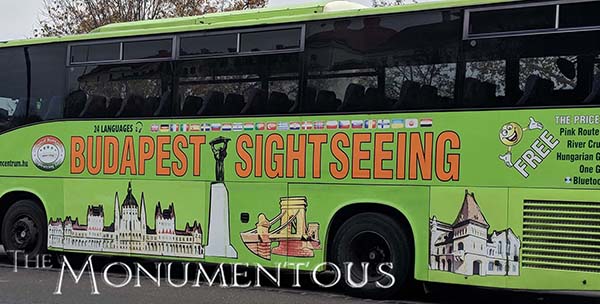

That impact is evident since the Liberty Statue has become a symbol of present-day Budapest, which can be seen in how the monument is positioned across the city. A symbol that represented a forgotten era wouldn’t have any place in images that depict the present-day city or be highlighted on trips and tours for visitors. The fact that the Liberty Statue can be and is included in all of these things and more showcases the notable impact it has had on the culture and economy of the region.

That impact is evident since the Liberty Statue has become a symbol of present-day Budapest, which can be seen in how the monument is positioned across the city. A symbol that represented a forgotten era wouldn’t have any place in images that depict the present-day city or be highlighted on trips and tours for visitors. The fact that the Liberty Statue can be and is included in all of these things and more showcases the notable impact it has had on the culture and economy of the region.

These transformative powers have their limits though, and it’s difficult to envision how the original Soviet soldier statues could be similarly transformed. Moving these pieces to Memento Park represents a powerful alternative to seeing them destroyed, as that history can be preserved, which allowed the rest of the Liberty Statue to be reinterpreted to better fit the present identity of the city and nation.

While the Liberty Statue might not have been erected to celebrate the independence, freedom, and prosperity of Hungary, the fact that it has been able to be transformed to commemorate all of those things is proof of how monuments can enable legacies that can become even more significant than their original purposes.

Illustrating the Transformative Power of Monuments

Effectively transforming or repositioning monuments of any size can be a difficult proposition, and the fact that the Liberty Statue was such a visible and iconic monument for Budapest made that transformation particular difficult. While opinions will always vary, the fact that Hungarians grew to love the statue enough not to remove it and enable this transformation speaks to how monuments can enable change and growth that is about much more than any physical changes to monuments themselves or the places they reside.

Effectively transforming or repositioning monuments of any size can be a difficult proposition, and the fact that the Liberty Statue was such a visible and iconic monument for Budapest made that transformation particular difficult. While opinions will always vary, the fact that Hungarians grew to love the statue enough not to remove it and enable this transformation speaks to how monuments can enable change and growth that is about much more than any physical changes to monuments themselves or the places they reside.