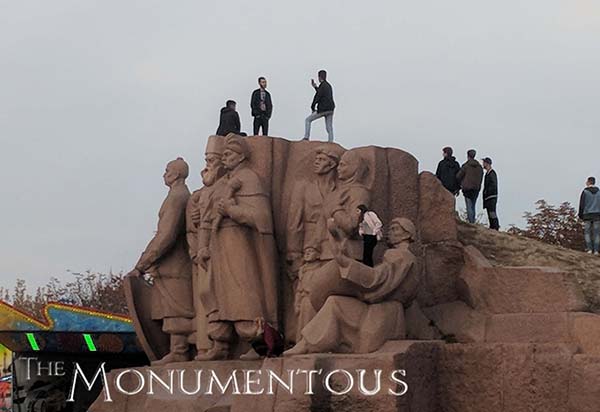

Monuments in Kyiv range from pieces that celebrate the national hero and founder of Ukraine to ones that honor and remember events that have helped shape the identity of the country. A variety of monuments that are obscure and outstanding are spread throughout the city, and they’ve proven to serve as powerful economic and social drivers for residents and tourists.

In addition to the people and events these monuments commemorate, they also reflect the history of the era in which they were installed. Monuments that were put up during the Soviet era (1922-1991) of Ukraine reflect this history in a way that has caused issues for the country in the present day, but it’s a conflict that these same monuments could help resolve.

Decommunization in Ukraine

After the fall of the Soviet Union, many of the post-Soviet states worked to define their own distinct cultural and social identities. For some, that resulted in a formal decommunization process, which saw the dismantling of communist state establishments, culture, and psychology that were present in the Soviet-era for many of the countries in the Eastern Bloc.

In Ukraine, this process started almost immediately with acts like the removal of the Monument of the Great October Revolution in 1991. The subsequent installation of Independence Square provided an incredible example of what the results of this process could look like, and was an inspiration for the official process that the country soon undertook.

In Ukraine, this process started almost immediately with acts like the removal of the Monument of the Great October Revolution in 1991. The subsequent installation of Independence Square provided an incredible example of what the results of this process could look like, and was an inspiration for the official process that the country soon undertook.

Decommunization laws were drafted in the Ukrainian parliament numerous times beginning in the early 2000s, and in 2015 four decommunization laws were passed. This started a six-month period for the removal of communist monuments and renaming of public places named after communist-related themes. The initiative was embraced by many throughout Ukraine as the country had 5,500 Lenin monuments in 1991. That declined to 1,300 by December 2015. By December of 2017, 51,493 streets, squares and “other facilities” had also been changed.

While successful and compelled by law, this decommunization process has also left some with conflicting feelings, especially when it comes to removing or changing monuments that showcase how Soviet symbolism and history have been embedded into Ukrainian culture.

The People’s Friendship Arch and The Motherland Monument

The People’s Friendship Arch was erected in 1982 and consists of three essential elements. The 50-meter, rainbow shaped arch that can be seen in various places in Kyiv is the most visually striking of these elements, especially at night. A large bronze statue underneath the arch depicts Russian and Ukrainian workers holding up the Soviet Order of Friendship of Peoples. The third element is a granite stele showing the participants of the Pereyaslav Council of 1654.

The Motherland Monument (Rodina-Mat) is similarly part of a bigger monument. The National Museum of the History of Ukraine in the Second World War contains pieces like “Crossing of the Dnieper, the “The Flame of Glory”, various weapons of war that were used in World War II, as well as a museum dedicated to the event. The Motherland Monument stands on top of that museum building and soars over 100 meters in the air.

Both of these pieces are tied to the Soviet-era of the country and have elements that strongly link them to this history and ideology. However, they have also come to serve as attractions for the modern country and formed identities that are very different from the era they were built. World War II monuments are excluded from decommunization laws, but in some cases, this just further complicates the issue of removal.

Since the Motherland Monument was created as a World War II memorial and currently houses a museum dedicated to the event, decommunization laws don’t apply to it. However, some still feel the piece should be torn down, and the shield still depicts the state emblem of the Soviet Union, despite plans to have it removed. The Arch of Friendship itself could be replaced, but many Ukrainians were the recipients of the Order of Friendship of Peoples award. Talk about removing them has some questioning whether the removal of such monuments does more harm than good.

The People’s Friendship Arch and The Motherland Monument are examples of the bigger history and cultural identity issues that are inherently part of this decommunization process, but they could also help define how such issues can be both addressed and acknowledged in a way that works for everyone.

Reimagining and Repurposing

For some monuments and in certain areas, the outright removal of a piece is the only way that the decommunization process can really happen. That was the case in Independence Square and is also the reality when a monument is toppled and destroyed. Given their history and recognition as attractions for the contemporary city, the outright removal of the People’s Friendship Arch and The Motherland Monument doesn’t seem ideal, which means that being able to reimagine and repurpose them could be beneficial for everyone.

As an example of how this kind of repurposing can work, the Ukraine House was originally built as a Kiev affiliate of the All-Union Lenin Museum, but today houses a very different kind of history along with all sorts of contemporary events that range from exhibitions to meetings to banquets. Additionally, some cities have modified their monuments, which not only allows these pieces to comply with decommunization laws but also allows them to serve as a completely new kind of attraction.

Changing the symbol on the shield of the Motherland Monument could be enough to repurpose the piece and enable it to better represent the entire history of the country, rather than a specific era. There are numerous national symbols of Ukraine that could be a fit to replace the hammer and sickle, and any alterations that incorporate something specific to Ukraine will go a long way towards seeing the piece fully repurposed.

Changing the symbol on the shield of the Motherland Monument could be enough to repurpose the piece and enable it to better represent the entire history of the country, rather than a specific era. There are numerous national symbols of Ukraine that could be a fit to replace the hammer and sickle, and any alterations that incorporate something specific to Ukraine will go a long way towards seeing the piece fully repurposed.

The People’s Friendship Arch would need a deeper reimagining since so much of what is depicted there ties to the Soviet-era for the city, and even to Soviet history itself. While the piece was originally created to commemorate the 60th Anniversary of the USSR, it also celebrated the 1,500th Anniversary of the Kiev city. A rededication of the arch to this event, along with new monuments that honor the Ukrainian People’s Republic and Independent Ukraine-eras could take the place of the monuments that are specifically tied to the Soviet-era. Those pieces could find new, more appropriate homes, to ensure the history they represent is not lost.

Regardless of what it will actually look like to reimagine or repurpose monuments like the People’s Friendship Arch and The Motherland Monument, efforts to do so will help create a legacy for Kyiv and Ukraine that sees the history of the area is remembered and built upon, rather than forgotten and destroyed.

A New Legacy for Ukraine

Being able to fully decommunize a city or region has proven to be more difficult in some places than others, and the effort has compelled questions about whether it’s even possible. The People’s Friendship Arch and The Motherland Monument are important examples of how monuments themselves could help guide and define what a city’s physical and figurative ties to the Soviet-era means to their present and for their future.

Being able to fully decommunize a city or region has proven to be more difficult in some places than others, and the effort has compelled questions about whether it’s even possible. The People’s Friendship Arch and The Motherland Monument are important examples of how monuments themselves could help guide and define what a city’s physical and figurative ties to the Soviet-era means to their present and for their future.

Despite these inherent difficulties, this process has been referred to as something that will allow Ukraine to “return to one’s true self”. It’s why potential and actual changes to the People’s Friendship Arch and The Motherland Monument represent a new and important legacy for the city and nation.