As the first major monument in Paris, the Paris Panthéon has been used for both religious and political purposes over the centuries, often alternating in quick succession between the two. These changes have not taken away from the Panthéon’s combination of gothic and classical principles that have helped create a monument that has become one of the most cherished by the people of France. The Paris Panthéon showcases what it can mean for a monument to honor the history and legacy of the nation while also attracting audiences from all over the country and the entire world.

As the first major monument in Paris, the Paris Panthéon has been used for both religious and political purposes over the centuries, often alternating in quick succession between the two. These changes have not taken away from the Panthéon’s combination of gothic and classical principles that have helped create a monument that has become one of the most cherished by the people of France. The Paris Panthéon showcases what it can mean for a monument to honor the history and legacy of the nation while also attracting audiences from all over the country and the entire world.

From Church to Temple to Monument

The space where the Panthéon resides has always been important, going back to 507 when King Clovis chose the spot to create a basilica to serve as a tomb for him and his wife Clothilde. In 512, Saint Geneviève, who would go on to become the patron saint of Paris, was buried in the Abbey Sainte-Geneviève, which was built in the 6th century.

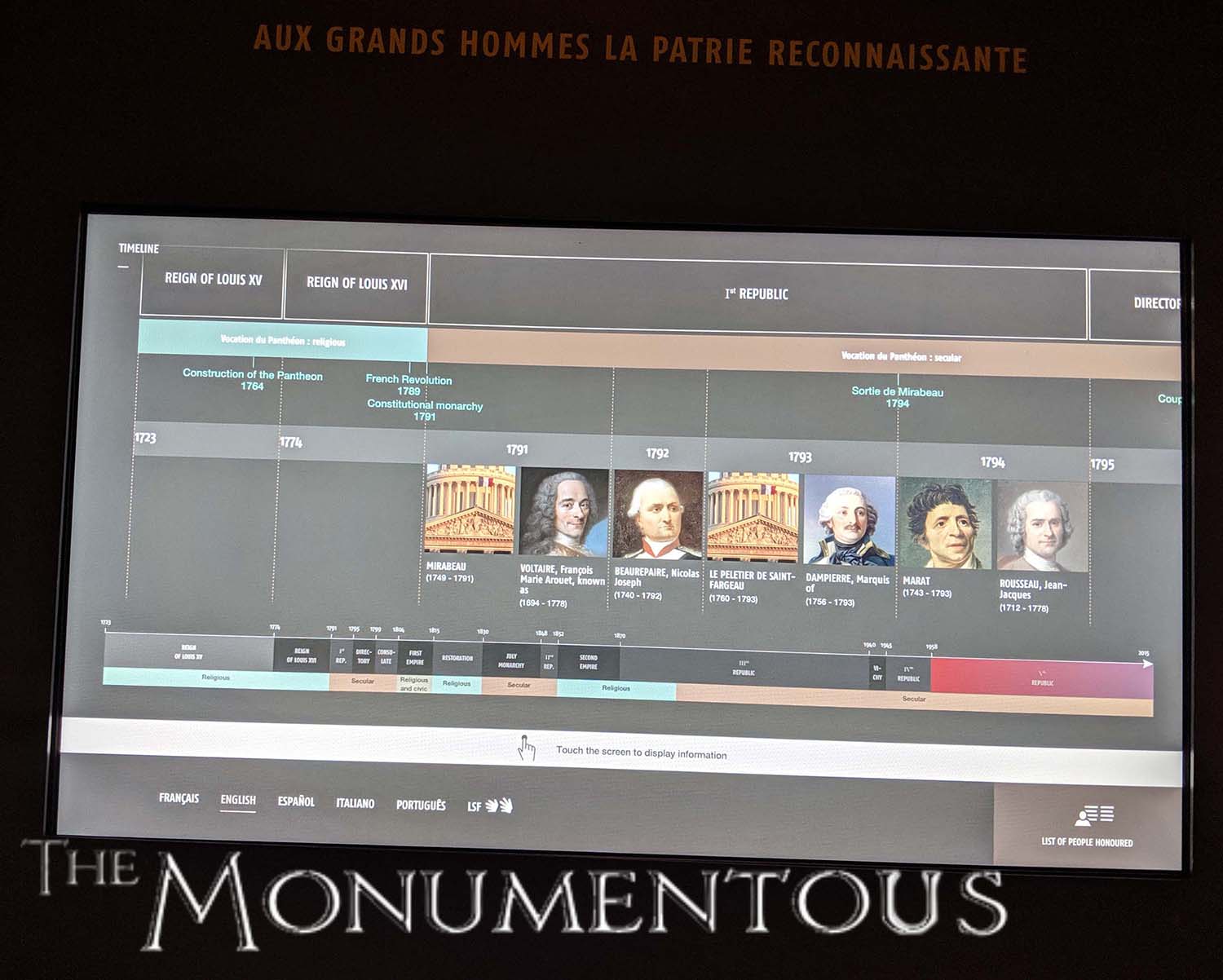

In the 1740s, King Louis XV vowed that if he recovered from an illness he would replace the abbey, which by that point was in poor condition. He recovered, but the effort to create a new church was not begun until 1758. A lack of funds prevented the building from being completed until 1790, at which point the French Revolution had begun.

The new leaders of the country had a different vision for the structure. The Constituent Assembly declared that the building would become a shrine to the heroes of France. It would “receive the bodies of great men who died in the period of French liberty.” Thus, it became the Panthéon, from the Greek word meaning the place where the gods live.

The ashes of Voltaire were placed in the Panthéon in 1791, followed by the remains of revolutionaries like Jean-Paul Marat and other notable Frenchmen, including Jean-Jacques Rousseau. During this time, some of the windows were bricked up to make the interior darker and more solemn and more fitting as a mausoleum.

The ashes of Voltaire were placed in the Panthéon in 1791, followed by the remains of revolutionaries like Jean-Paul Marat and other notable Frenchmen, including Jean-Jacques Rousseau. During this time, some of the windows were bricked up to make the interior darker and more solemn and more fitting as a mausoleum.

Napoleon became First Consul in 1801 and soon after the Panthéon reverted to being a church dedicated to Genevieve. However, it was switched back to a crypt under the restored monarchy of Louis-Phillipe in 1830. More political upheaval saw the Panthéon become “The Temple of Humanity” in 1848 but then restored as a church under Napoleon III not even a decade later.

In 1881, a decree was passed to transform the Church of Saint Genevieve into a temple that honored French luminaries once more. Victor Hugo was the first to be placed in the crypt in 1885. Subsequent governments have kept the Panthéon as a temple to the culture and legacy of France, with many others being buried over the decades, including five influential women.

While the Panthéon has become and continues to be a repository for the remains of great French citizens, the experiences it has enabled for visitors from France and elsewhere have enabled it to become far more than a mausoleum or crypt.

Experiencing the Interior and Crypt of the Panthéon

The exterior of the Panthéon features a facade that is modeled after the Panthéon in Rome. It also features a sculpture with distinguished scientists, philosophers, statesmen and soldiers. Below the sculpture is the motto: “To the great men, from a grateful homeland.”

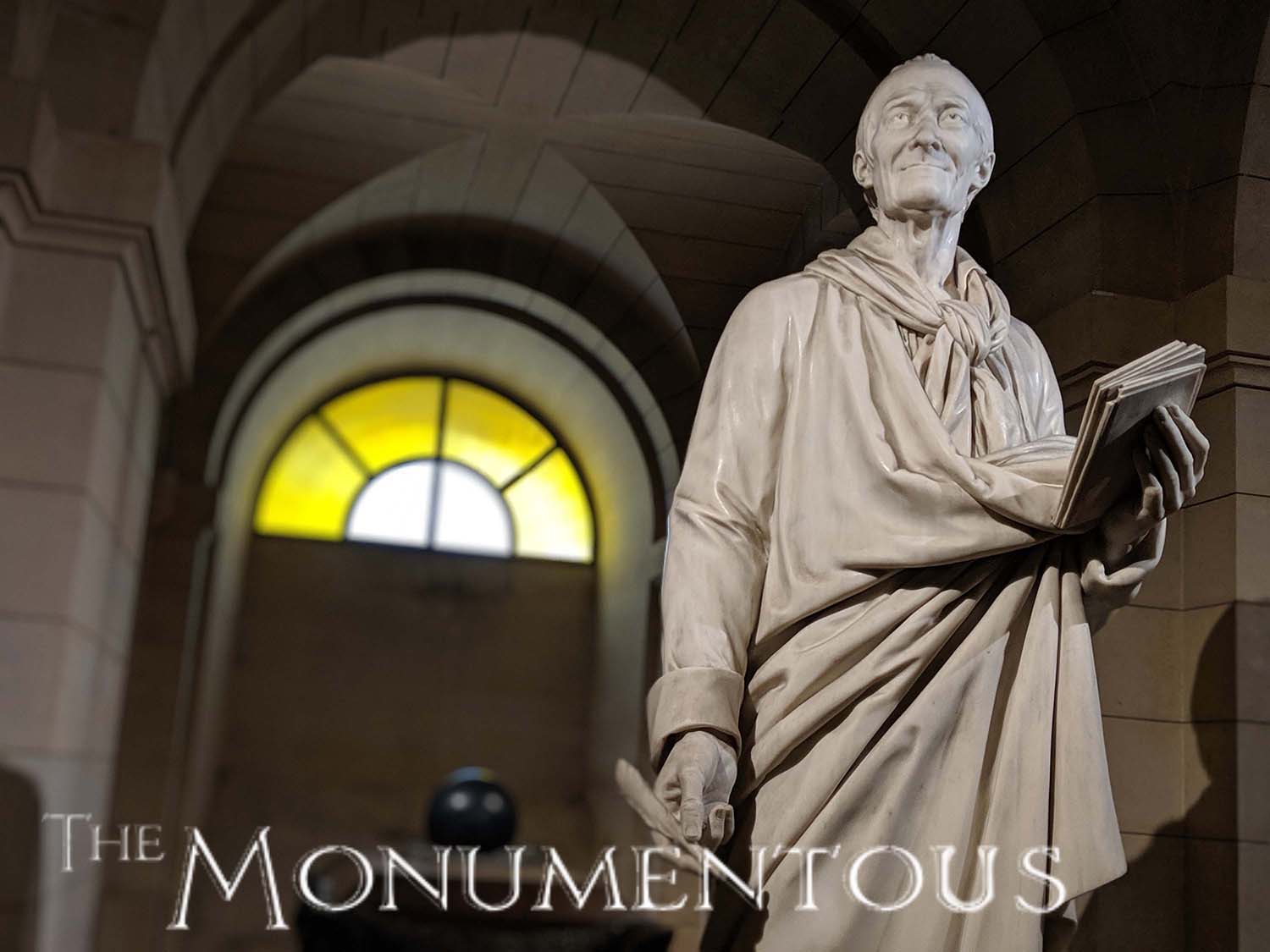

The Paris Panthéon has two major sections inside. The first is the interior of the building itself, which features an incredible combination of Gothic decorations that mesh with the classical style of the building itself. Its neoclassical exteriors are inspired by ancient Roman architecture, whereas its dramatic interiors are indisputably French Gothic.

The Paris Panthéon has two major sections inside. The first is the interior of the building itself, which features an incredible combination of Gothic decorations that mesh with the classical style of the building itself. Its neoclassical exteriors are inspired by ancient Roman architecture, whereas its dramatic interiors are indisputably French Gothic.

The dome of the building is actually three domes, and unlike the Dome des Invalides, it is made entirely of stone. The dome is also accessible and provides visitors with a panoramic view of the city. Although it is not as high as other observation platforms in Paris, the location of the Panthéon puts viewers in direct line with the Eiffel Tower.

This interior is where Jean Bernard Léon Foucault held his famous experiment in 1851 that proved that the world spins on an axis. That actual pendulum was moved to the National Conservatory of Arts and Crafts but a replica remains on display at the Panthéon amongst painted frescoes, mosaics and paintings. These pieces depict Saint Genevieve, key moments of French history, notable French figures and scenes from the French Revolution.

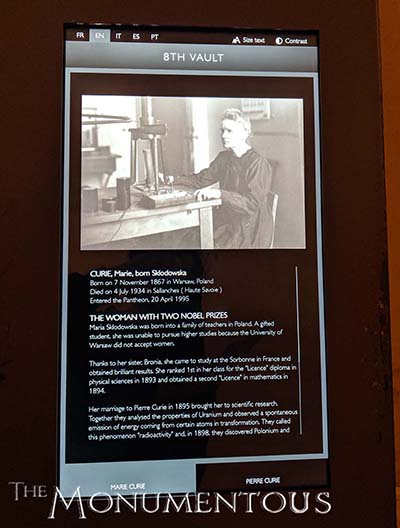

Beneath this interior is the crypt, which contains the remains of Émile Zola, Jean Jaurès, Pierre and Marie Curie and Jean Moulin, just to name a few. Permanent exhibitions and interactive displays give details about the lives and works of all the people who are buried in the Panthéon.

The features and experiences of the Paris Panthéon have directly fueled numerous economic opportunities, all of which are built upon the Panthéon’s identity as an essential icon and element of Paris culture and the French society as a whole.

An Icon of Paris and France

Tickets for independent tours can be purchased from the Panthéon in a variety of ways, although visitors can get in free the first Sunday of the month from November 1st through March 31st, highlighting an important way that the Panthéon engages with the community. Entry to the Panthéon is also free with a Paris Insiders Pass, further showcasing what it can mean for cities and monuments to combine experiences that further engage audiences.

Guided tours are also offered every day in the afternoon, providing a general tour on the Panthéon and its history. Tour-lectures are also available in numerous languages alongside a variety of ticket offerings. The Paris Panthéon also houses a gift shop and bookshop, providing another important means of direct revenue.

Outside of the Panthéon, numerous businesses have been built up and around the landmark. Many utilize the imagery and icon of the Panthéon itself to attract audiences. In becoming such an important and recognizable icon of Paris and France itself, the Panthéon has come to showcase the power of icons to drive and create incredible economic opportunities.

Outside of the Panthéon, numerous businesses have been built up and around the landmark. Many utilize the imagery and icon of the Panthéon itself to attract audiences. In becoming such an important and recognizable icon of Paris and France itself, the Panthéon has come to showcase the power of icons to drive and create incredible economic opportunities.

Such opportunities stem from the effort to honor some of the most important individuals of the French nation. By creating a suitable place that could house multiple heroes of France, the Panthéon highlights what it can mean for a landmark to both celebrate and build upon a legacy for the benefit of individuals and entire cities and countries.

Celebrating the Past and Future of France

Considered to be a top monument in a city that contains countless landmarks, the Panthéon has become a real attraction for residents and visitors that can be appreciated and experienced in multiple ways. Residents and French citizens can get a better sense of their heritage, while visitors can get a better context of important history and people from a whole new perspective.

Considered to be a top monument in a city that contains countless landmarks, the Panthéon has become a real attraction for residents and visitors that can be appreciated and experienced in multiple ways. Residents and French citizens can get a better sense of their heritage, while visitors can get a better context of important history and people from a whole new perspective.

Other monuments and memorials celebrate the history of an area or event, but few are as complete as the Paris Panthéon. In becoming a temple of France itself, the Paris Panthéon highlights what it means when a monument embraces a legacy that extends into both the past and future.