Composed of two distinct monuments, the Cuarto Centenario Memorial in Albuquerque, New Mexico was created to commemorate the 400th anniversary of New Mexico’s founding. However, the process around selecting who and what the memorial would depict became contentious, and the final piece powerfully represents how monuments can represent the past and present of an entire community in multiple ways.

Composed of two distinct monuments, the Cuarto Centenario Memorial in Albuquerque, New Mexico was created to commemorate the 400th anniversary of New Mexico’s founding. However, the process around selecting who and what the memorial would depict became contentious, and the final piece powerfully represents how monuments can represent the past and present of an entire community in multiple ways.

A Journey in the Past and Present

In 1996 a group of citizens in Albuquerque advocated for a sculpture that celebrated the six-month trek of Spanish families to establish the northernmost boundary of New Spain, which would eventually become New Mexico. The original proposal was to create a simple bust of Don Juan de Oñate, who led this journey, which would then be placed in the Old Town neighborhood. The sculpture was to be completed in time for New Mexico’s 400th birthday in 1998.

In 1996 a group of citizens in Albuquerque advocated for a sculpture that celebrated the six-month trek of Spanish families to establish the northernmost boundary of New Spain, which would eventually become New Mexico. The original proposal was to create a simple bust of Don Juan de Oñate, who led this journey, which would then be placed in the Old Town neighborhood. The sculpture was to be completed in time for New Mexico’s 400th birthday in 1998.

Views around the legacy of Oñate have continues to change and evolve though. He has long been honored in the region for bringing Spanish culture to it, but he was removed from his position for mistreating Pueblo Indians and abusing his power. He also declared a “war of blood and fire” on Acoma Pueblo, one of the oldest continuously inhabited communities in the United States. Some view him as the historic founder of the area, while others think of him as little more than a brutal conqueror.

In December of 1997, three artists were asked to help create a piece that would represent both Hispanic and Native American perspectives to address some of these issues. However, Betty Sabo and Reynaldo “Sonny” Rivera had much different ideas than Nora Naranjo-Morse. The original idea was that the three would work on a single memorial, but Sabo and Rivera eventually settled on a sculpture series that would depict Oñate leading the first group of Spanish colonists into New Mexico, while Naranjo-Morse wanted to create an abstract land art installation made out of the desert itself.

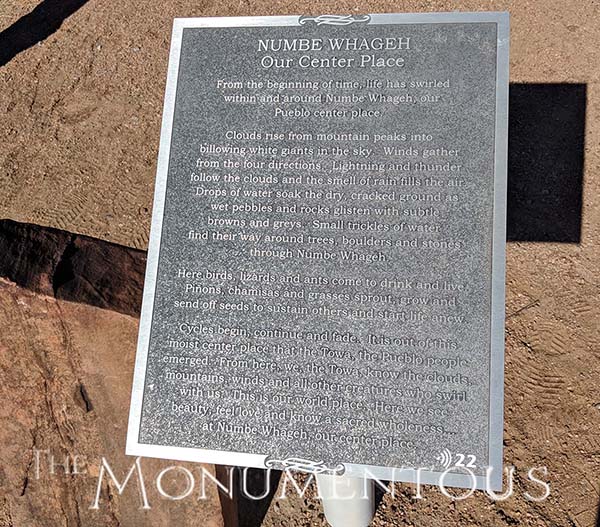

These ideas and perspectives could not be reconciled, which is why the Cuarto Centenario Memorial is actually comprised of two completely different memorials. “La Jornada” (the journey) displays more than two-dozen life-sized bronze figures that represent the settlers headed northward in 1598 and would eventually establish the first capital of New Mexico. A piece representing Juan de Oñate is up front, leading the group. Across from it, “Numbe Whageh” signifies the Native American perspective and is far more abstract. A large dirt spiral resides in the middle of, taking viewers down into the Earth until all they can see is the dirt.

These ideas and perspectives could not be reconciled, which is why the Cuarto Centenario Memorial is actually comprised of two completely different memorials. “La Jornada” (the journey) displays more than two-dozen life-sized bronze figures that represent the settlers headed northward in 1598 and would eventually establish the first capital of New Mexico. A piece representing Juan de Oñate is up front, leading the group. Across from it, “Numbe Whageh” signifies the Native American perspective and is far more abstract. A large dirt spiral resides in the middle of, taking viewers down into the Earth until all they can see is the dirt.

The Cuarto Centenario Memorial was not completed in the year of New Mexico’s 400th anniversary but was finally dedicated in 2005. The contentious process that saw what was supposed to be a simple memorial turn into an entire installation that takes up most of a city block showcases the power of monuments to inspire communities and elicit feelings about history, culture and identity.

Two Memorials, Many Perspectives, One Monument

Like other sculpture series that are dedicated to a specific event, La Jornada is designed to capture the emotion and action of the moment. Men and women as well as children and animals are depicted trudging up a hill, as if they’re in the middle of their northward march. Many view the journey of Oñate and these other settles as an important part of New Mexican and American history. The family names of the six hundred people who embarked on this journey are inscribed on the wall that surrounds La Jornada.

Like other sculpture series that are dedicated to a specific event, La Jornada is designed to capture the emotion and action of the moment. Men and women as well as children and animals are depicted trudging up a hill, as if they’re in the middle of their northward march. Many view the journey of Oñate and these other settles as an important part of New Mexican and American history. The family names of the six hundred people who embarked on this journey are inscribed on the wall that surrounds La Jornada.

Numbe Whageh does not depict any specific figures or event, and instead represents something far more intangible from the perspective of Native Americans. Numbe Whageh means the center place, or the place of the earth. A plaque near the piece says that it is from this center place that the Pueblo people emerged. The earth sculpture spirals inward to a small spring at the center, which is where the Pueblo people, identified as the Towa, see beauty, feel love and know a sacred wholeness.

The juxtaposition of Native and Western perspectives has made the subtext of the community and region actual text, which has helped to create a dialogue among citizens. Students, teachers, residents and visitors debate history and cultural relationships in a way they wouldn’t otherwise discuss. These two approaches have provided physical form to a contested history, and present very different approaches when it comes to remembering and representing New Mexico’s colonial past.

The Cuarto Centenario Memorial has come to define the space in an especially powerful way, as it occupies the north end of the Albuquerque Museum grounds which contains a sculpture garden. It is also directly across from Tiguex Park, which provides a venue for soccer, family gatherings, celebrations, performances, and a variety of other special events. The entrance to Albuquerque’s Old Town is also nearby, allowing the Cuarto Centenario Memorial and the discussions it has cultivated to become a hub of activity for the city.

The Cuarto Centenario Memorial has come to define the space in an especially powerful way, as it occupies the north end of the Albuquerque Museum grounds which contains a sculpture garden. It is also directly across from Tiguex Park, which provides a venue for soccer, family gatherings, celebrations, performances, and a variety of other special events. The entrance to Albuquerque’s Old Town is also nearby, allowing the Cuarto Centenario Memorial and the discussions it has cultivated to become a hub of activity for the city.

The literal representation of a clash between cultures illustrates what it can mean when a monument becomes about something much more than bronze and dirt. The Cuarto Centenario Memorial showcases what happens when the legacy of history and identity is reflected on in the present in order to positively influence the future.

A Complicated and Evolving Legacy

Many monuments are being reconsidered in the present, but the Cuarto Centenario Memorial is unique because it hasn’t been forced to deal with the kind of reevaluation that many other monuments have to experience. The piece literally depicts the marginalized perspective that has compelled so many of these revaluations, but that depiction has also become part of the legacy for the area that is both complicated and evolving.

Many monuments are being reconsidered in the present, but the Cuarto Centenario Memorial is unique because it hasn’t been forced to deal with the kind of reevaluation that many other monuments have to experience. The piece literally depicts the marginalized perspective that has compelled so many of these revaluations, but that depiction has also become part of the legacy for the area that is both complicated and evolving.

Ultimately, the Cuarto Centenario Memorial speaks to perspectives and disagreements in the present that have their roots in a situation that first arose 400 years ago. By literally depicting this clash in both figure and form, the piece demonstrates the power monuments can have to influence how communities consider and guide such legacies into the future.